Andreas Vesalius was born in Brussels either in the last few hours of 1514 or the first few of 1515 (Nutton, 2003). He came from a family of prominent physicians, fifth in a chain of fathers passing on the medical profession to their sons (Fisch, 1943a); his father held a position at court as the apothecary to Emperor Charles V.

As a young man, Vesalius received an elite Humanist education. In 1528, he first left Brussels to attend the Castle School at the University of Louvain where he followed the typical course of study for a wealthy young man of the time, which focused on rhetoric, philosophy and logic. From there he decided to follow the family tradition and study Medicine, leaving in 1533 for the University of Paris, the top medical school in northern Europe. When war broke out in 1536 between France and the emperor, Vesalius was forced to leave Paris before he could finish his degree. He completed his medical studies at the University of Louvain and took his MD examinations in Padua in 1537.

By the end of those first years studying medicine, Vesalius had already managed to earn a reputation for his skill as a dissector (Saunders & O’Malley, 1950). Because practical dissection was neither taught to students nor highly valued as a skill, Vesalius had to learn the art by his own initiative. He practiced dissecting animals on his own time. And, if this story recounted in Saunders and O’Malley’s (1950) introduction to their

The Illustrations from the Works of Andreas Vesalius of Brussels is at all indicative, Vesalius probably did not scruple from making his own opportunities to practice on the real deal:

While out walking, looking for bones in the place where on the country highways eventually, to the great convenience of students, all those who have been executed are customarily placed, I happened upon a dried cadaver . . . I climbed the stake and pulled off the femur from the hip bone. While tugging at the specimen, the scapulae together with the arms and hands also followed, although the fingers of one hand, both patellae and one foot were missing. After I had brought the legs and arms home in secret and successive trips (leaving the head behind with the entire trunk of the body, I allowed myself to be shut out of the city in the evening in order to obtain the thorax which was firmly held by a chain. I was burning with so great a desire . . . that I was not afraid to snatch in the middle of the night what I so longed for. (p. 14)

In any event, Vesalius’s reputation as a dissector and student of anatomy was such that, upon passing his exams, he was immediately offered a faculty position at the University of Padua.

As a professor at the university, Vesalius became a vocal champion for the art of dissection, making it a regular part of his lectures. At the time, it was unusual for professors to perform their own dissections, but Vesalius made a name for himself by descending from the professor’s lectern to personally dissect and demonstrate on all of his own cadavers. His lectures became so popular that students, professors and educated members of the public alike crowded his dissection theatre. He introduced a further innovation by augmenting his demonstrations with large, detailed illustrations and charts, which he went on to publish. While many leading physicians opposed these illustrated anatomies, claiming that it “had not been done in classical times and would degrade scholarship” (Saunders & O’Malley, 1950, p. 16), they quickly became popular study aids among students and pirated versions appeared throughout Europe. In these early publications, with their use of high-quality, detailed illustrations and findings about human anatomy gleaned from direct observation, the germ of Vesalius’s great work, the

Fabrica is evident.

Vesalius likely began work on the

Fabrica in the winter of 1539-1540, completing it in the summer of 1542, and publishing it a year later. With more than 80,000 words and over 200 illustrations, it is a massive work to have been completed in such a short time and by such a young man; Vesalius was just 28 years old when it was published. The work put forth two radical ideas: first, that Galen’s anatomy, which had been considered authoritative, was deeply flawed because Galen had primarily used nonhuman sources; and second, knowledge of human anatomy could only be gained through direct observation of the human body, chiefly by means of dissection. These challenges to the

status quo were met with resistance and the initial response to the

Fabrica was so poor that Vesalius tragically burned all of his notes for the work and all the materials he was preparing for future publications in a fit of disappointment (Saunders & O'Malley, 1950).

Vesalius and the

Fabrica had some powerful admirers though. It was published in June of 1543 and shortly thereafter, Vesalius was granted an audience with the emperor, Charles V. At this meeting, Vesalius presented the emperor, to whom the

Fabrica is dedicated, with a specially prepared, illuminated copy of the book with each illustration hand-painted by a highly skilled miniaturist. The emperor was so impressed that he immediately took Vesalius on as a court physician.

As a member of the court, Vesalius was expected to give up his work as a scholar and maintain a low profile. It is unclear why Vesalius chose this route. Perhaps, it had always been his intention and the

Fabrica was a simply a means to an end. Court held many attractions, among them wealth, prestige and a chance to mingle with the great minds of the age. It also was an opportunity to actually practice medicine and Vesalius had always been interested in becoming a complete physician, skilled in the surgical arts (Saunders & O’Malley, 1950). Whatever his reasons might have been, by accepting the emperor's offer, Vesalius essentially gave up his research at the height of his academic career. While his life at court was eventful and Vesalius gained respect across Europe as a physician, none of his later achievements ever matched that of the

Fabrica.

In 1564, for mysterious reasons, Vesalius made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. On his return, he was caught in a storm and shipwrecked on a Greek island where he fell ill and at just 50 years of age, died. Vesalius's body was buried on the island and there is perhaps something fitting about Vesalius making his final resting place in the homeland of Galen, to whom he owed so much.

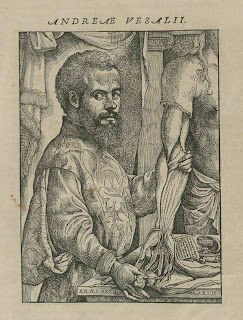

Andreas Vesalius's exhaustive anatomical study of the human body, De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem invites superlatives. Published in 1543, it is easily the most famous, most influential and most beautiful anatomical work ever created. With more than 200 magnificently detailed woodblock illustrations, the Fabrica combines scientific method, text, illustration and typography in a wholly new way that revolutionized the study of anatomy, elevating Vesalius to the ranks of physicians like Hippocrates, Galen and Lister and earning him the title: Father of Modern Anatomy.

Andreas Vesalius's exhaustive anatomical study of the human body, De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem invites superlatives. Published in 1543, it is easily the most famous, most influential and most beautiful anatomical work ever created. With more than 200 magnificently detailed woodblock illustrations, the Fabrica combines scientific method, text, illustration and typography in a wholly new way that revolutionized the study of anatomy, elevating Vesalius to the ranks of physicians like Hippocrates, Galen and Lister and earning him the title: Father of Modern Anatomy.